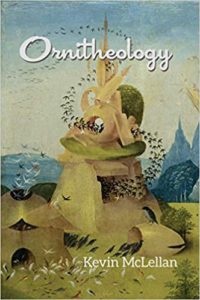

Kevin McLellan’s Ornitheology

Ornitheology by Kevin McLellan. The Word Works, 2018. 90 pages. $17.00

by Nate Vaccaro

Ornitheology is Massachusetts-based poet Kevin McLellan’s fifth book of poems. The title tricks the reader at a glance into believing the book is about the scientific study of bird, but the addition of an E quickly subverts first impressions. Abounding with the events of the everyday, hallucinations, observations, tributes, and of course, birds, Ornitheology is a book of second-glances and rereading, where meaning is slid under meaning, weaving a theology of interlocking poems.

McLellan builds a foundation for Ornitheology out of tributes to other poets. The first section, Sentinel, contains poems which honor Sylvia Plath, John Keats, James Schuyler, and Ariana Reines, and McLellan often invokes lines of their work within his own poems. The poems also follow in the tradition of McLellan’s own body of work, as this isn’t the author’s first run-in with our feathered friends. In Tributary, McLellan’s 2015 book of poetry published with Barrow Street Press, birds also appear as a myriad of signals, symbols, and signs. In “Remarks on Nomenclature (a tribute)” from Tributary, the lines “100’s of birds (species unknown) land // on this leafless tree (species also unknown) / outside my (Homo sapiens) window” (47) contain elements echoed in the lines of “Quills” from Ornitheology which read, “I neglected to feed them, the birds (species / unknown) that lived in my imagination” (34). The species of the birds, real or imagined, is still unknown, but the self-species is known. While the world remains mysterious, McLellan’s poems ceaselessly interrogate, through both outward and inward reflection, the spaces between fact and imagination.

The second section of Ornitheology, Quills, honors poet Kazuko Shiraishi, borrowing language from her poem “It Was a Weird Day.” The sequential poem shifts between the natural and the urban, the understandable and the mistaken. It begins with a bird death in the first section:

Guilt the entire day for not helping

a pine siskin I watched hard-smack

a window and fall fifteen or so feet

to cement steps.

The center of her

organizing and a light sleet gives

voice to downed leaves. (33)

The image is sharp and momentary, one small hard-smack at the focal point of an entire day’s guilt. Ornitheology is filled with little moments like these: light hitting carpet, a paramedic bleaching the sidewalk, a honking car. Each instance is considered and noted, the poems exploring the crushing significance of any single occurrence in our daily lives.

The final section of the book, Crown, begins with an epigraph from Gertrude Stein: “Everyone gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense.” The sentence seems as though Stein could have written it in a Tweet in response to an article about the negative mental health effects of social media instead of in 1946 while reflecting on the atom bomb. Nowadays, for better or for worse, we are more saturated with information than ever before, our personalities split between digital and physical realities, fake and real news, truth and alternative truth. This final section, a sonnet crown in 14 parts, dedicates each respective poem to some convention of trickery. There is the hallucinogenic imagery of the 11th sonnet, “Schisms,” where “cherries are people and regrettably / I’ve forgotten their names” (77), and the acceptance of confusion in the 7th sonnet, “The Last Days in June,” where the speaker says, “I want to make sense of this / and then don’t” (73). Stein’s prophetic quote sets the backdrop to not only the whimsy of the final section but also the book as a whole. Ornitheology, in all its dizzying flights, is perhaps the only natural way to respond to the world’s current gluttony of information.

From a bird’s-eye view, the poems in Ornitheology are concentric to the book’s own theology. They are connected within their own references, blurring the lines between self and other, life and death, replete with concepts as intangible as eschatology and as personal to the reader as the memories associated with the smell of Windex. Even as McLellan’s poetry rests on the excruciating importance of details, as in “Portland,” where “for dinner // some ramen noodles // with an unbroken yolk / like the sun I remember // when I had all of me /” (55), there are also moments of depersonalization. In “After the Biggest Give,” the speaker says, “When asked my name yesterday / I said sunshine for the to-go falafel. / I don’t know what to believe anymore” (75). After reading (and rereading and rereading) McLellan, you become certain in your uncertainty, begin to believe in your unbelief. Every encounter becomes significant, every bird (species unknown) becomes an unsolved mystery and an answer, and every experience is stripped down to the act of witnessing nature and self, death and life. And those, perhaps, are the founding doctrines of ornitheology.

Buy a copy of Ornitheology here.

Kevin McLellan is the author of the full-length poetry collections, Ornitheology (The Word Works) and Tributary (Barrow Street). He also authored the book objects, Hemispheres (Fact-Simile Editions) and [box] (Letter [r] Press), the chapbook Round Trip (Seven Kitchens Press) and his poetry appears in numerous literary journals. His prose appears in Jelly Bucket, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, Lily Poetry Journal, Orca, Superstition Review, Timber, and Waxwing. Kevin is also Duck Hunting with the Grammarian Productions and his video, Dick (2020) appeared in the Tag! Queer Shorts Festival. Kevin lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Nate Vaccaro is a non-binary poet and literary essayist currently living in Rhode Island. Their creative work interrogates the relationships between LGBTQ identity, the internet, and the potentials of the written word. With a background in literary scholarship and rhetoric, they explore the intersections and boundaries within LGBTQ writing, fashion, theory, and experience through poetry, essays, and multimedia methods.