A REVIEW OF MARC VINCENZ’S THE PEARL DIVER OF IRUNMANI

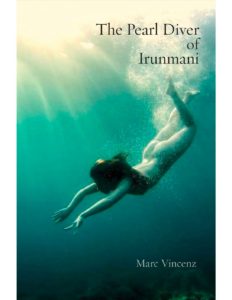

The Peal Diver of Irunmani, Marc Vincenz. White Pine Press, 2023. 120 pages. $17.00

by Steven Cramer

On first looking into The Pearl Diver of Irunmani, Marc Vincenz’s new poetry collection, perhaps not every reader would Google the word “Irunmani.” I would and did, and came up with scores of websites featuring the book itself, before my browser asked if I might prefer a search for Iron Man. My quest wasn’t fruitless, however: a Borgesian tautology—Irunmani means Irunmani—makes for an illuminating first dip into this collection of refracted light. Like one of Calvino’s invisible cities, the mythical province of Irunmani—never summoned in the book again—gives the poems an indeterminate, if richly populated, locale. Stevens called such a region without coordinates “an invented place in an imagined world.”

Eliding incident or back-story, the watertight poems Vincenz has crafted over thirty years and published in over twenty books are usually rigorously compressed, unfriendly to blurted confidences or chatty digressions. In The Pearl Diver of Irunmani, the prosody shaping these austerities derives from the free-verse inventions of the early 20th-century Modernists. A kind of genomic mix of early Stevens and Williams, Vincenz’s verse in this book often deploys a two- or three-stress measure, with syncopated end-stopped, parsed, and enjambed line endings, as in Intensive Care Unit, the third and final section of “Stories Seen in the Carvings”:

Vaguely abysmal, the city,

though our earthly architect

did his very best,

something’s amiss—

the rattle of the furnace,

the hum of the vent

sends that hollow howl

through the inside of

the room . . .

While the terse rhythms typify Vincenz’s style, the tilted mirror held up to “the so-called world” (cummings) does not. We find few furnaces, vents, or even rooms in The Pearl Diver of Irunmani. Instead, the poems tend toward prismatic moods and tones—vistas obscured by mist or blurred by distance, shape interchangeable with motion, appearances looming then disappearing, a perceptual fluidity the same poem calls “the ruse of a wandering life.” Even among the rattle and hum of the ICU, bedside talk takes the form of controlled hallucination, where “words dressed in lemon/and mint float inside the mind.”

To further induce in readers the mental state Freud named the oceanic feeling—in which “the ego detaches itself from the external world”—throughout the book Vincenz disperses fifty-five italicized, untitled fragments, bits of verbal driftwood, some moored to a left or right margin, some cast adrift on an otherwise blank page. Thirty-five of these tiny islands (by my count) allude to water, in imagistic brush-strokes—The brine, the gusts, a game of sea creatures; as Delphic injunctions—Follow the squall, a gentle trail, into the pitch; and occasionally as gentle comic relief—This is Forever: the tuna chasing minnows. Given all these encounters with depths, eddies, finned creatures, foam, gulls, pools, spray, and waves, it’s fair to say that one doesn’t read The Pearl Diver of Irunmani so much as dive in and swim.

But it’s on the level of the line, the word, and even the syllable that Vincenz’s studied detachment and rich verbal textures make for a poetry of spare but undulating beauty:

A grazing of dust in this

tranquil, quilted time

Eyes unseen, unknown.

Seaslugs and curled shells

moving in slow-postured mastery.

(“Filled Out with Moonlight”)

This clash of incompatible attributes—dust in the realm of seaslugs—is pure Vincenz, as is the last line’s lovely snail’s pace of rounded vowels. The long syllables wade waist-deep through shallows, Vincenz’s auditory imagination both ascetic and lush. (It’s rare these days to hear a poet who’s attuned to the prosody of stress and duration.) There’s also a more impure Vincenz, whose poems remain strict even as they misbehave. Still evincing the cool rigor that informs the book, the first sentence of “Mysteries” takes the reader on a joyride of subordination:

Suspended in the blue-white sky,

threatened from beneath

by those fist-wielding locals,

(a bird as the word of a god)—

and just as they had been washing

their feet, the seepage of

the stagnant water

and the burning black cloud of oil—

Curtains! they roar

in that guttural, centuries-old tongue,

clinging to the edges,

like summer snows on

mountain chains—transcendent

in their wetlands, their harsh marshes.

Never mind who the loudmouth “they” are (gulls appalled by an oil spill?); or what pisses off the “fist-wielding locals”; or from which etymological roots “that guttural, centuries-old tongue” grows. The pleasure these lines afford comes more from their rhetorical dexterity than from clear-cut details or legible images. Step back, and the punchline at the heart of the syntactical maze comes clean: the shaggiest of Hollywood mobster clichés (hard not to pronounce the word as coit-ins). The magician spinning this web of a sentence may dress in black tie, but he’s also an expert jokester.

When not pulling skeins of syntax out of a hat, Vincenz’s poems can execute pitch-perfect riffs in his characteristically taut free-verse tempo:

Somehow we

still feel

the sea’s will.

Love should be born

out of this gloss

of blackness,

and yet we want to

climb out

to see a sky

the color of water

and trees, trees

everywhere.

(“Now the Moon Sinks Too”)

Each stanza here offers its own sonic or rhetorical pleasure: the interplay of long and short vowels and liquid consonants in stanza one; the modulation to rounded vowels, sibilance, and alliteration in stanza two; and—most striking to my ear—the sequence of parsed and enjambed lines traversing the last two stanzas, striving line-by-line toward resolution, which occurs when a spondaic repetition—trees, trees—overlaps with the closing line break: trees/everywhere. However obliquely the passage limns a natural terrain, it’s the emotional tenor—feel, love, want—and the verbal music of its vehicle, that creates the poem’s richly expressive total effect.

In one of the book’s darker interstitial snippets, Vincenz removes the mask of impersonality: “perhaps I am the only ghost to haunt this place” (surely a nod to late Stevens’s doleful self-talk at age seventy: “I wonder, have I lived a skeleton’s life”). “Karma,” the poem this epigram footnotes, is among my favorites in the book, its manner more ambivalent than ambiguous, still oblique in circumstance but palpable with feeling:

How the birds have stopped singing,

how the green has become gray,

how your last words resonate

—this is the very thing you are.

A short note from the heart.

I could still hear his laughs

from where while reading

at the kitchen lamp, the night

was windowless and the words

split apart as the housefly drilled

into the cracks. . . .

No, we don’t learn why these autumnal lines elegize “your last words” or recall “his laughs”; indeed, neither pronoun recurs. What impels the speaker later in the poem to describe himself as “afraid of what it meant/to be orphaned, to be departed” remains mysterious, as does “how the nearsighted cloud in the pane//has little fear of the unknown.” The poem’s resolution, with its first-person plural—“we were//reborn again, every second/Sunday among the birds”—completes its emotional trajectory, reviving its governing emblem, but it doesn’t provide a narrative denouement. A poet whom Vincenz resembles in no other way (despite a short lyric provoked by his work), John Ashbery offers a fruitful approach to reading a poem like “Karma”: “watch the thing that is prepared to happen.”

The poetry of awareness is not the same thing as the poetry of ideas. The latter ruminates; the former meditates, as figments of perception and thought come and go within the clearing house of mental life. Some commentators call Vincenz a philosophical poet. Twenty-plus books abounding with Air, Earth, Fire, and Water invite—and indeed, reward—the kind of thematizing that invokes the Truth of the Imagination, Mortality and Transcendence, the Ineffable, Suffering and Redemption, and other big nouns. I’m more drawn to Vincenz the artisan of lyric attention, alert to consciousness and its contents, resistant to paraphrase but inhospitable to theory. Incuriosity never reads poetry well, but too much ado regarding what Vincenz’s poems are “about” can miss their poetry. Asked by a seatmate on a long flight what her poems were about, Heather McHugh curtly replied: “they’re not about about.” The poems in The Pearl Diver of Irunmani move me less for their putative concerns and more, much more, for their sequent effects, best captured in verbs: they perplex, beguile, seduce; and perhaps most saliently, they transport.

Steven Cramer’s seventh collection, Departures from Rilke, will be published by Arrowsmith Press in fall 2023. His previous books include Listen (MadHat Press, 2020), named a “Must Read” by the Massachusetts Center for the Book; Clangings (Sarabande Books, 2012); and Goodbye to the Orchard (Sarabande Books, 2004), a Sheila Motton Prize-winner and a Massachusetts Honor Book. He founded and currently teaches in Lesley University’s Low-Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing.