A REVIEW OF KIMBERLY ANN SOUTHWICK’S ORCHID ALPHA

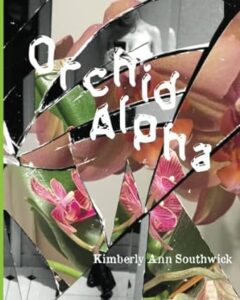

Orchid Alpha, Kimberly Ann Southwick. Trembling Pillow Press, 2023. 108 pages. $16.99

by Jessica Bowdoin

“Desire Pinned to the Page”: A Review of Kimberly Ann Southwick’s Orchid Alpha

Unfiltered and full of dark humor, desire, and sexual energy, Southwick’s debut poetry collection, Orchid Alpha, unpacks the id of the modern day woman. The speaker flirts with the edges of gender constructs and social boundaries, between “being good” and inviting indiscretion. Played out in acrylic bathtubs and hotel bars, on hay farms, in the midst of psilocybin hills, ghost tours, and alone on blown up air mattresses, it isn’t always sex that’s desired but rather connection, excitement, and a giving in to “the wilderness, [as] it enfolds me, & I consent” (80).

Mythology and folklore connected to desire and motherhood are reexamined through allusions to Eve, Demeter, Mother Leeds, and the moon, as a symbol of evolving desire: “wax hard gibbous” or else “wane sharp & crescent” (62). Even art is given new agency in Southwick’s poem, “The Birds, The Birds,” as “Eve’s public hair runs golden, invisible,/ gathered at the tip of her cunt like a hint or an invitation,” while Adam looks up and away at “his God,” in her ekphrastic poem on Bosch’s The Earthly Delight (69).

The way she weaves in these allusions, often with modern interpretations, makes them funny and relatable. I too would do much worse than Mother Leeds if I were forced to have 13 children with a man “who bought me in a sale/ barely distinguished as impoverished love/ to clean feed sew nurse cook” (79). And this mother of a monster is seemingly connected to another mother of monsters, the first Eve: Lilith, whose story of sexual dissatisfaction and rejected inferiority was buried under the story of the Fall. Southwick, in the last poem of this collection, “Immaculate Reception,” asks of the apple, “like the one Eve shared with Adam—why do we say tempted /as though it were more than FUCK, THIS FRUIT IS DELICIOUS & IMPORTANT? why / do we say forbidden as if god didn’t know all along he wanted us out of the garden?” (81). Southwick’s questions related to religion and the role of temptation and desire in modern society press on gender stereotypes and assumptions. Women, with all their desires and impulses, all their humanness, are no different than men. Our differences are societally, and often religiously, constructed.

A personal definition for desire also unravels throughout the 59 poems of this collection. There are two major relationships: a love story that tracks a complicated marriage and a lust story of perilous and exhilarating desire. The speaker is drawn to her impulses in both relationships; she straddles gender expectations and sexual liberty in equal measure. The title of the collection becomes a representation of this duality, as Orchid Alpha mixes the symbolism and image of the exotic flower as female genitalia with the word alpha, which in pop culture and nature has come to represent aggressive masculinity and power. Yet, in this collection, the combined “orchid alpha” becomes a symbol of feminine sexual power, and phone sex with her lover becomes an outlet:

the pulse of my orchid alpha, its petaled claws, is why

I look so good in these shorts meant for someone ten years younger

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

for him to draw me into his web, I think of myself as the spider,

waiting in a mess of sticky silk. the way he asked,

do you like that, so quiet & wrong in my ear, still

wrings me out, how he sounded so relaxed on the phone, disorienting (28)

Sonically beautiful and tantalizing, “Suck It In,” describes a speaker that is willing to capture herself on behalf of her lover. This paradox between prey and predator becomes the basis of an existential question that boomerangs throughout the collection: whether choice and control or lack of control is the origin of desire and ultimately love. Here, she must “think of [her]self as the spider” and plays the role of the submissive despite the knowledge that she is the alpha. Likewise, in “Kriegspiel,” she confesses, “…I want/ to be taken advantage of but with my own consent/ is that a contradiction…” (67). This push and pull of control and her tendency to give into desire is the speaker’s predilection and ultimately complicates her decisions related to sex and marriage.

Yet, she is a realistic picture of the unmasked modern woman; she inhabits gender expectations but also undermines them. Stereotypical conceptions of love are confronted, and there aren’t any unrealistic fairytale poems hidden in the seams of this collection. Though, later when the lover is gone and her husband is centered in the narrative, desire evolves into a deeper love in the face of nostalgia, guilt, and stubbornness. The speaker’s persistent and genuine connection with her husband eventually circumvents the memories of her past, though their own story is more serpentine than arrow.

Their story plays out in a series of domestic landscapes in the South. She describes one of their homes as “a trailer on a hay farm,” with “the rolling Gulf Coast thunder,” the both of them on “two dark roads, hiccupping home” to where “mosquitos are born to puddles/ & flies floss bedroom lights, their patterns tracing the bulb” (34-35). Her natural imagery is exceptionally beautiful, but it’s also concrete and recognizable, as she recounts the late summer song of cicadas, the towering pine trees, the azaleas, dense humidity, and even the dead possum their dog unexpectedly murdered and dragged through the kitchen. The way Southwick constructs her settings in these poems creates a strong sense of place that contrasts with the settings portrayed with her former lover, in hotel rooms, cabs, and other temporary spaces. This seems wholly intentional and so do the sonics of these poems that intensify, that become song-like, as they corrupt and inhabit their contemporary sonnets.

In these poems, the speaker’s love for her husband often contradicts her rules for control. He is not portrayed as perfect nor always the object of her desire, and unlike the lover, their relationship is not coded as a form of escapism. Rather, like many couples, they simply struggle to connect and communicate, to have good sex, to pay their bills, and to not take their love for granted. Here, the mundane and domestic become a catalyst for boredom and nostalgia. Memories and old impulses reappear. Old promises to former lovers are questioned. Yet, forgiveness and intention supplant these impulses as well as jealousy and anger. The speaker is left to question exactly how she has arrived here:

…someone tell me what it is i deserve

for these long-tabled indiscretions what my

punishment must be please then give it to

me oh one cup of soothing bayleaf tea

a clutch of forsythia picked from our yard

delivered in a small handmade vase the sound

of rain heavy on the awning yes I know that is

not what I was thinking I meant either. (68)

There is such authenticity that sits in the weight of the word “deserve.” How can he offer his kindness? How can she accept it without guilt or reservation? How can this relationship be what either of them “deserve”?

These questions sit at the heart of this collection as the humanity behind our desires cannot be ignored. Loving a partner requires us to accept their flaws as well as the wax and wane of our desire for them, “because love is defined through sacrifice & narrative, pain/ & participle, theater & labor” (45). Love, even self love, must prioritize stability which requires hard work, and so the speaker becomes her own star and reference point and then, by the end, they are one “reference point, our own star in our own constellation,” despite “no money or god or government” (39, 81). This is the point between ephemeral impulse and love’s longevity, though desire, in its perpetual duality, inhabits both skies.

So, whether a modern and relatable love story is preferred or a manifesto about desire through the lens of art, mythology, astronomy, and psychology is sought after, this debut poetry collection is a worthy read. Southwick’s poetry does not shy away from the impulses of the subconscious nor its swarming insecurities. She has written a collection that most women can relate to and that some men should probably take the time to read. With such honest and artfully written poetry, Orchid Alpha sets the bar for Kimberly Southwick’s future collections, and readers and editors should pay attention to this poet’s writing in the future.

Jessica Bowdoin is an English professor, writer, and Autistic poet. She received her MFA from the University of New Orleans in 2023. Currently, she is working on a poetry collection which redefines social and clinical language used for neurodivergent individuals and addresses the double consciousness which stems from social “othering.” Some of her other work examines the intersection of disability and sexual violence against women. She won the 2022 Vassar Miller Award for Poetry, was a finalist for Inverted Syntax‘s 2023 Sublingua Prize for Poetry, and received honorable mention for the 2023 Andrea Saunders Gereighty Academy of American Poets Award. Her work can be found in Beyond Queer Words,Inverted Syntax, Backchannels Journal, Ellipsis, and elsewhere. Connect with her on Instagram (jessica_bowdoin), X (@jnbowdoin), or at jessicabowdoinpoet.com.