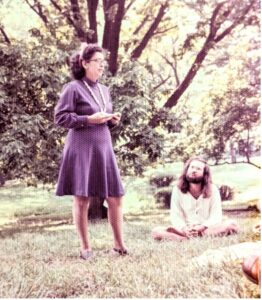

Rosemary Cappello, poetry reading in Fairmount Park,

Philadelphia, 1974[1]

Four Poems by Rosemary Cappello, featured in the new Ocean State Review

Windows

One of the bad things about being

a secretary is you never get a window.

The lawyers I work with all have bright

offices overlooking an atrium.

When my boss calls me for dictation,

as I go from my dark corner to his sun-filled

office, I feel like a bat let out of a cave.

I have to tell him my eyes must

adjust to the sunlight

before I can begin.

Sometimes, I toy with the idea

of going to law school

just so I can have a window.[2]

*

May City Heatwave

It’s hot

and smells of rain tonight

no creek in sight

no drooping foliage

the bricks reach

far from Eden

my fig tree

on the balcony

confronts the bricks

and fattens in the heat

*

When I die,

bury me with a still life,

a real still life, of

strawberries, apples, grapefruit,

oranges and figs—

mostly, figs

*

Anyone who writes about

depression as well as you do

she wrote in answer to my depression

her letter and mine now gone

I don’t remember what I had

written so well about depression

I don’t remember the rest

of her reply

I just remember that when

I wrote the letter

it was snowing

and the snow was beautiful

*

Rosemary Cappello (1935-2022), Poet of Peace by Mary Cappello

“There must be a special grace in having a poetry-producing mother.” From an e-mail from a

friend, writer, Shifra Sharlin

My mother, the poet, Rosemary Cappello, believed in the power of literary journals, and of poetry, to change the world. Of course she was a lover of books, inveterately so, but she reserved a special place on her shelves for literary journals where many voices, many moods commingle; where micro-communities and collectives are forged; where the aura of the times in which we live is marshalled for the sake of future enlightenment.

In poems, words meet in novel ways inside a line; in reading them, so do people meet in ways they never could have imagined.

My mother believed in the ways that writing and art make new forms of friendship possible.

My mom always called herself a “pacifist.” It’s a word that we hardly hear anymore, a self-descriptor we were more likely to recognize, in this country, at least, during the period of the War in Vietnam, or what the Vietnamese called the American War. No matter that we’re still, as a country, steeped in war, aiding and abetting lasting harm in the Middle East, the word seems to have fallen out of use as an identity category, a point of pride, a way of life, and even the basis of an Art.

If a “pacifist” is a person who is implicitly anti-war, pacifist might be another word for poet, which is not to say that we turn to poetry as pacifier or opiate. At its best, poetry doesn’t quell the rage or soothe the agitation; it revolutionizes language as rallying cry in their stead.[3] It enables start and startle; it quickens the ear and incites the tongue. It does all of this while simultaneously inviting the calm required by meditation as the ground for compassionate acts.

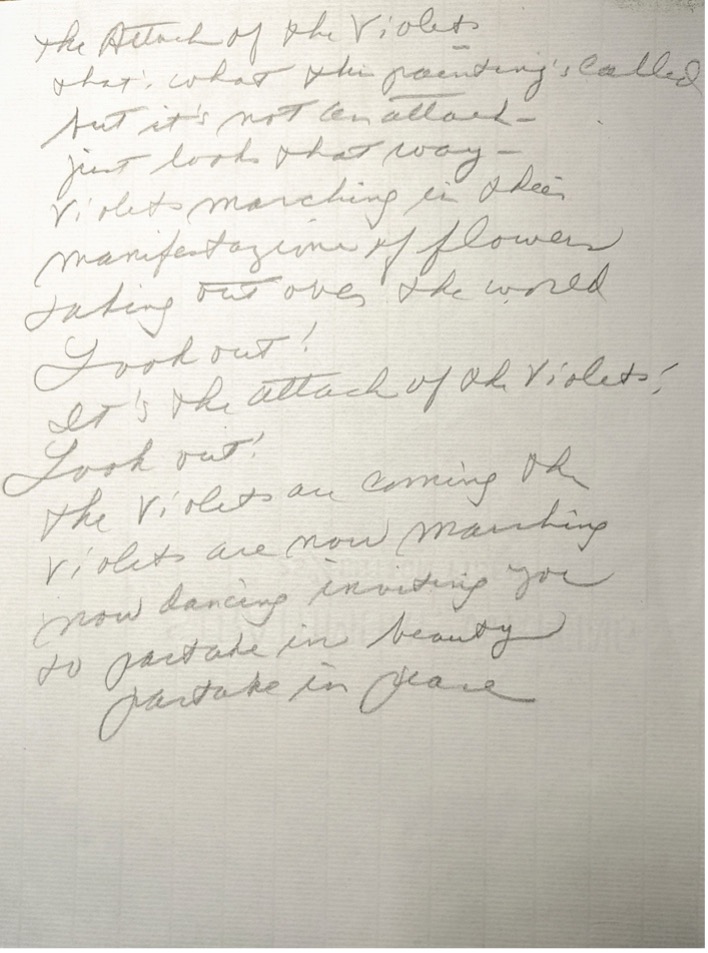

My mother was a self-taught water-colorist and painter of what she called “energies” whose canvasses occasionally also gave rise to poems. After my mother died, as I sifted through hundreds of paintings and thousands of poems, I discovered a timely one that she must have written late in life, hand-written in pencil, as clear accompanist to a painting that hung on her walls. The painting is called Dreaming in Blue, and it hung in my mother’s bedroom; she titled the companion poem, “The Attack of the Violets.” It’s a piece by a pacifist in war-defining times.

Dreaming in Blue (2017), Watercolor, 30 x 39’

The Attack of the Violets

That’s what the painting’s called

but it’s not an attack—

just looks that way—

violets marching in their

manifestazione of flowers

taking over the world

Look out!

It’s the attack of the violets!

Look out!

The violets are coming the

violets are now marching

now dancing inviting you

to partake in beauty

partake in peace

The near rhyme of violets and violence isn’t lost on me, nor the Italian word for “protest” as that which manifests (see also manifesto/manifesti), nor the hilarity of “look out!” ‘cause who knows what might happen if we allow ourselves to be attacked (which in this poem means disarmed) by peace; who knows what might happen if we allow ourselves to be attacked by the love we so apparently fear.

Rosemary Cappello, my poet-mother, believed that poetry could make things happen; she believed in poetry as a form of magical thinking, not to be confused with delusion, but more the mad capture of the dream that reality aims to tamp or skirt. An inveterate keeper of notebooks and, from a very young age, an avid letter-writer, my mother composed poems that bear the traces of both of these forms. So many of her untitled poems (like these two in OSR) remind me of random notebook entries, a spontaneous art alive with the quotidian, the poem as time-bound happening, a stilled point of yearning inside the chaos. The direct address of her work always leaves me feeling that I’m in receipt of one of her pan-harmonious letters. (As her numerous correspondents, from close friends to strangers, knew, she brought the lowly form known as “e-mail” to a place of high art, and transformed FB “posts” into narratives alive with associative meandering, comfortingly compelling as a Prairie Home Companion but recollected by an urban, East Coast feminist).

The poems that are featured in this issue of OSR exemplify some of the character of Rosemary Cappello’s overall aesthetic and larger body of work, not least, an attention to negative space and the art of subtraction. My mother, all her life, managed to create whole worlds out of small spaces (a corner of a dining room in Darby, PA, where she wrote a great deal of her poetry; a corner of her bedroom in Center City, Philadelphia, where she brought her literary annual, Philadelphia Poets, lovingly into being; an apartment balcony where she made her garden, to say nothing of the indoor shelves on which she cultivated all manner of plants for the ages). She saw the poet in everyone she met, she listened for and heard the worth and power and wonder of other people’s words—their art—then gave them a home in Philadelphia Poets’ pages or in the community spaces where she brought people together to proclaim, converse, and eat, and drink, and share.

If you didn’t know her, you couldn’t know she was a person of radical openness; oh, but you can find those qualities in the poems—they’re immensely personable and readable. To follow her voice across the course of a book, like her Wonderful Disaster (Bordighera Press, 2021) [4]is to be met with an exquisite sensibility, very Italian, that moves at the pace of an Italian passagiata, the undistracted stroll of a Sunday afternoon, even when life doesn’t allow for such; it’s in love with the daily; it’s often ironic; it conjoins high art and the vernacular; it’s essentially lyrical; in it, you feel the presence of a supremely particular soul, or what my friend, Karen Carr calls my mother’s “sun-soaked orbit.”

My mother was a “naturalist’s poet,” by which I mean that her style was natural (spontaneous, fresh, unadorned, pure) and she tuned herself daily to the gifts bestowed on her perceptions by what we might call “the natural world,” the world of fruits and flowers, earth and sky. (Many a day since her passing, I’ve imagined how much the natural world misses her, she doted on it so.)[5]

Poems like these that appear in OSR offer a glimpse of this sensibility:

a poetry, as spare as it is exorbitant;

the poem as a devotional practice and an ode to joy;

a poetics of meditative rapture.

My mother taught me that to make art is fundamentally to remain hopeful and to love life; poetry as a form of prayer.

My mother taught me that for every experience in life, there is a song—there is a poem; my mother’s voice was always singing, old standards, show tunes, operatic arias, or in times of need, reciting Coleridge’s Rime (which she knew start to finish), lots of Longfellow (which she’d also memorized), the entire Catholic mass in Latin (that, she didn’t recite, but whose rhythms and ritual informed her verse alongside Gregorian Chant even after she’d left the Church). She was reared on the poetry of Petrarch, Dante, Neapolitan folk music, and the history of Italian opera, bequeathed her by her shoemaker father whose formal education had not gone past eighth grade. She sought her own influences in everything from Blues and bebop to the paintings of the Chinese minimalist, Ch’i Pai Shih (Qi Baishi).

Wherefore her signature tone, rye, deadpan and churlish as a Dorothy Parker? It’s there in the elliptical ending of “when I wrote about depression”; it subtly smacks you and laughs in “The Window.”

It’s all over her notebooks’ one-liners:

“We know what’s not good for us, but we pray for it anyway.”

“It’s time to throw out the dead roses he didn’t give me.”

…It’s funny when it waxes haiku-ish:

After freeing the prickly pear

from choking weeds,

get out the tweezers. What

Ingratitude!

*

Asking for Mint Tea

but getting Sencha—

Zen misunderstanding

*

…It’s fierce when it faces things squarely (or roundly):

My life

Rolls toward me.

I step aside and

Move on.

…It’s tucked inside poem-riddles laced with grief:

MY NEW LIFE

Nine and a half months of

mourning-

I could have a two week old

self by now.

but the gestation

of a new me

seems to be taking

longer than usual.

Maybe it will take two and a half

years, the gestation period of

the elephant, who never forgets

The ironies that light these poems from within rely, of course, on the unspoken subtleties that the poems both signal and forge, but sometimes in a poem’s search for justice, tones that are playfully arch, tones that bespeak a kind of graceful acceptance and restraint, morph into full-fledged take-downs of their subject.

“On Listening to Bach’s Magnificat” is a poem I only found after my mother’s death. I never heard her read it at a reading, and I’m not even sure she’d want for me to share it, but I love it for its irreverence, an adjunct to the fervor that inspires the poems as a whole. My mother taught me that the f-word was cheap and easy and therefore best avoided in literary art; invective is born of desperation, and desperation is the opposite of poetry, the opposite of thought. She taught me to use such words sparingly, if at all, but here she uses it, I think, to fucking great effect:

ON LISTENING TO BACH’S MAGNIFICAT

Christmas

sorting out mentally what was done

in the recent and remote past,

reading the umpteenth article

attributing Christmas stress to

men not helping women

and no money to buy gifts

when it really comes from the idea itself;

do we believe this, that a child was born as a result of

“he that is mighty” doing “great

things” to “his handmaiden”?

Face it, it’s that whole fucking story we’re force fed

that chokes us every Christmas,

but who will deny the baby’s adorable

and so are the cherubs

and don’t forget loyal Joseph with his

symbolic lily staff, unlike the staff of “he

who is mighty,” the one with the “great thing.”

It’s cruel. The

baby is born

to die

as are we all, but his death

is slow, torturous, mean, and

leads countless others to live lives that are

slow, torturous, mean

even though he spoke so much of love.

Too much contradiction.

Well, time to plug in the lights.

A daughter can “see” things in a mother’s art that others might not—I think that this is true. I look to others to see further still.

Rosemary (Petracca) Cappello (October 8, 1935-September 13, 2022) was a poet, painter, prose writer, revered community organizer, and founding editor and publisher of Philadelphia Poets. One of her first chapbooks, The Habit of Wishing, appeared in 1977 in collaboration with Ann Menebroker and Joan Smith. Numerous chapbooks and hundreds of published poems later, her first full-length collection, Wonderful Disaster, came out with Bordighera Press around the time of her 84th birthday. She believed that poetry’s most important and lasting impetus is love; she gave encouragement and voice to scores of writers in her lifetime; and she enjoyed the translation of her work into other languages and other media, including music and visual art. This BIO was provided by her daughter, writer and URI Professor Emerita, Mary Cappello. When she was alive, Rosemary preferred the following BIO: “Born. Grew./Grew? Grew./Grew? Grew./Not through.”

Mary Cappello is a queer practitioner of the essay, experiments in prose, memoir, literary nonfiction, and performative criticism. Her seven books include a detour on awkwardness; a breast-cancer anti-chronicle; a lyric biography; a speculative manifesto; and the mood fantasia, Life Breaks In. A former Guggenheim and Berlin Prize Fellow, she is Professor Emerita of English and Creative Writing at the University of Rhode Island.

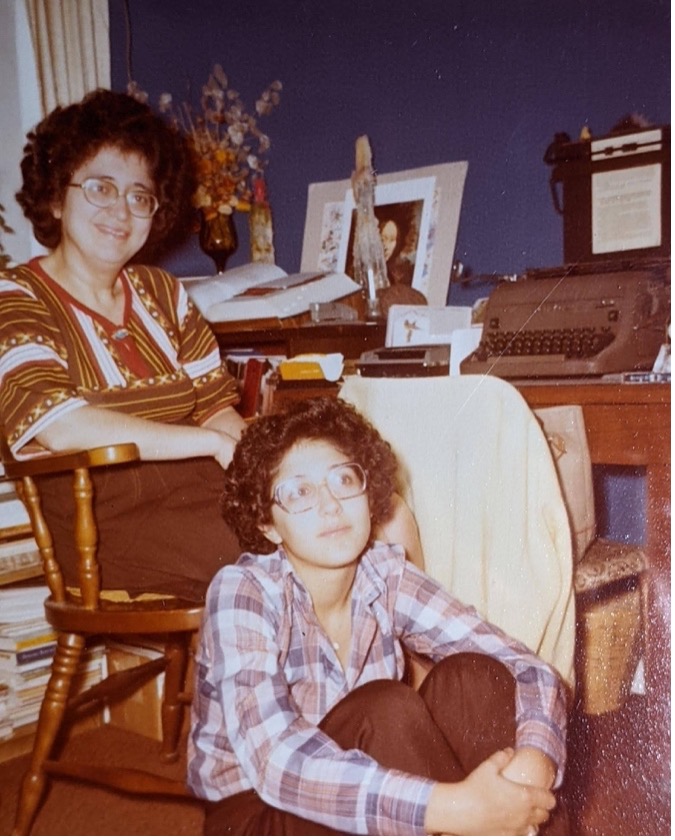

Rosemary Cappello and Mary Cappello circa 1977

[1] This photograph of my mother reading in Fairmount Park was taken by poet and photographer, Joel Colton, whose distinctive work and all too short life is described here on poet, Don Yorty’s indispensable on-line archive. The day-long “poetry picnic” in September 1974 featured dozens of poets over the course of the day. It was my mother’s first poetry reading and took place one week after the devastating loss of her father. According to the program, my mother hosted the event alongside her close friend, the poet and, later, beloved children’s book author, Eileen Spinelli (then, Eileen James), and, Steve Pike. The day was punctuated by music by my brother and me who were teens at the time and closed with a Sing Along.

[2] “Windows” is part of a series of “work” poems. My mother often composed poems as part of series, rounds, and cycles. The work poems also include a series of “lay off” poems after my mother lost her job. Other thematically-driven series are focused on the nature of gifts; the death of Sid Shupak, her partner of many years, “The Sid Poems”; snow poems; November poems; to name a few. “The Actress” hails from the “work” series.

THE ACTRESS

(in homage to Loretta Young)

You had to admit

there was something special about her,

the way she walked into a room

wearing Edith Head clothes like

no one else-

You had to admit

no one else was able to be

so slender, so lithe, yet

captivate a space-

You wanted to be like her,

walk into a crowded room

and do your own special

walking dance to unheard

music fluttering your gown

And you are like her

Every day when you get off the

elevator in the foyer of the

law firm where you work and you

twirl around once

for the receptionist

[3] Shifra Sharlin’s remarkable essay, “Better Practices in Mourning,” which I only recently discovered while re-perusing back issues of The Southwest Review (vol. 94, no. 3/2009) in my study, inspires me to think of these matters afresh. The essay—a deftly interwoven gloss on grief and on Russian Formalism—reminds us of how futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov “invented a new language so that words could be restored to what he considered their original function: namely to ‘dispel enmity and make the future transparent and peaceful,’ because ‘[n]owadays sounds…serve the purpose of hostility.’ War puts our social lives at risk” (370) “…War estranges life more than art could; but Shklovsky never says that war makes art superfluous or impossible” (369).

[4] The titular poem of the collection is part of a series of prose poem love poems based on her having become romantically involved with a man who was (a robust) 11 years her senior when she was 78: “Falling in love, at my age, with you, at your age, is a disaster, but a wonderful disaster.” December 8, 2013

[5] Here’s a favorite exemplification, for me, this homage to green:

MY GREEN THUMB

People say I have a green thumb and I say

how can this be, when I don’t even have a garden,

until they point out the thirteen plants

thriving on my window sills.

We’ve been living together for many years,

these plants and I, and before they came here,

one was my mother’s, another was my father’s,

and yet others were my sister Jo’s. My most recent

addition is my begonia, a true treasure.

Recently my daughter

joined the chorus and told me I have a green thumb, and I said, why

do you say that, and she replied because you don’t feed your plants, and

look at them! But I water them, I remarked. And I also care for them very deeply.

I think that’s what a green thumb is—a love of nature so strong that one actually

starts to turn green, as green as a leaf in summer, as green as a desert cactus, as

green as my shiny begonia, so green, so beautiful, it begs to be painted in all its green

glory.